News | Posted April 22, 2025

Guest Blog – Translating the Past: History & its Images in Late-Medieval Scotland

‘For when one sees a story illustrated whether of Troy or of something else, he sees the actions of the worthy men that lived in those times, just as though they were present.‘

Richard de Fournival, Le Bestiare d’amours.

The illustration of manuscripts containing historical material offers important insights into late-medieval historical understanding and the conception of a collective identity or idea of nationhood. The role that images played in formulating identities and ideologies in Scotland has received little sustained investigation, however, examining the visual material in illustrated manuscripts helps us to understand how medieval readers were constantly rethinking and revisualizing the past in terms of their own present.

One section of my current book project, Scotland on Parchment, deals specifically with this idea; of how Scottish manuscripts interpreted historical material in visual terms. In comparison with continental manuscript traditions, the study of Scottish material throws up one major hurdle and that is simply that there is a much smaller corpus of surviving examples to work with and fewer still might be described as fully illustrated. The key exception to this is the extraordinary Cambridge Scotichronicon (CCCC MS 171A and B). However, despite the evidence being somewhat thin, where images do survive, they provide valuable evidence for understanding how Scottish history was read and understood during the late-medieval period.

Even the very word often employed during this period to refer to manuscript illumination, historiated draws out this important connection between history and the visual image in a manuscript context. It is, therefore, important to carefully consider what we mean by the word ‘history.’ Whilst we might define the term, as a chronological record of significant events often recorded with an explanation of their causes, in the Middle Ages the meaning was rather more flexible. Histoire or estoire had a range of meanings and interpretations including the recording of real and/or imaginary events, and this recording could be done with words (written or verbal) and/or images (painted, sculpted or woven). The flexibility of the terminology and its ability to encompass real and imagined pasts is significant.

Whilst we may be lacking a large corpus of extensively illuminated historical material, such as survives for the French tradition of the grandes chroniques de France, nevertheless images were certainly present in the Scottish historical tradition. Whilst the Cambridge Scotichronicon (CCCC. MS 171A and B) provides us with the most extensive pictorial evidence (this manuscript forms a key source for the book project), there are other examples of visual material in Scottish historical manuscripts and much of this has hitherto gone unrecorded. Since these other histories are not illustrated in the traditional sense, we need to cast our net a little wider – all visual material is significant after all.

We might take an example that I recently examined in the British Library, a Scotichronicon manuscript: MS Royal 13 E.X. This is a parchment manuscript of 278 folios at 44 × 29cm. It is datable to after October 1447 and before the death of Nicholas V in 1455 and was evidently copied from CCCC MS 171. This manuscript, MS Royal 13 E.X., belonged to Paisley Abbey in 1502 and it is often, on account of this, referred to as the Black Book of Paisley. has been described as an ‘eccentric production’ (Watt, vol 9, 187) due to various omissions and errors and it contains scribal activity by at least two late-medieval readers. What has not previously been examined before, however, is the visual marginalia in relation to the textual additions. The images, although few and far between, are of great interest. Two significant examples of such imagery are a marginal sketch of a raised sword on f.77v and a fox on f.173r (Figs. 1 and 2).

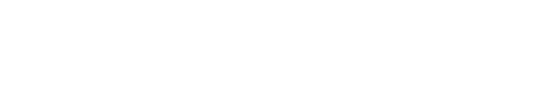

- Fig 1. A raised sword (f.77v) from the Black Book of Paisley, B.L. MS Royal 13 E.X. (Image Credit: Bryony Coombs)

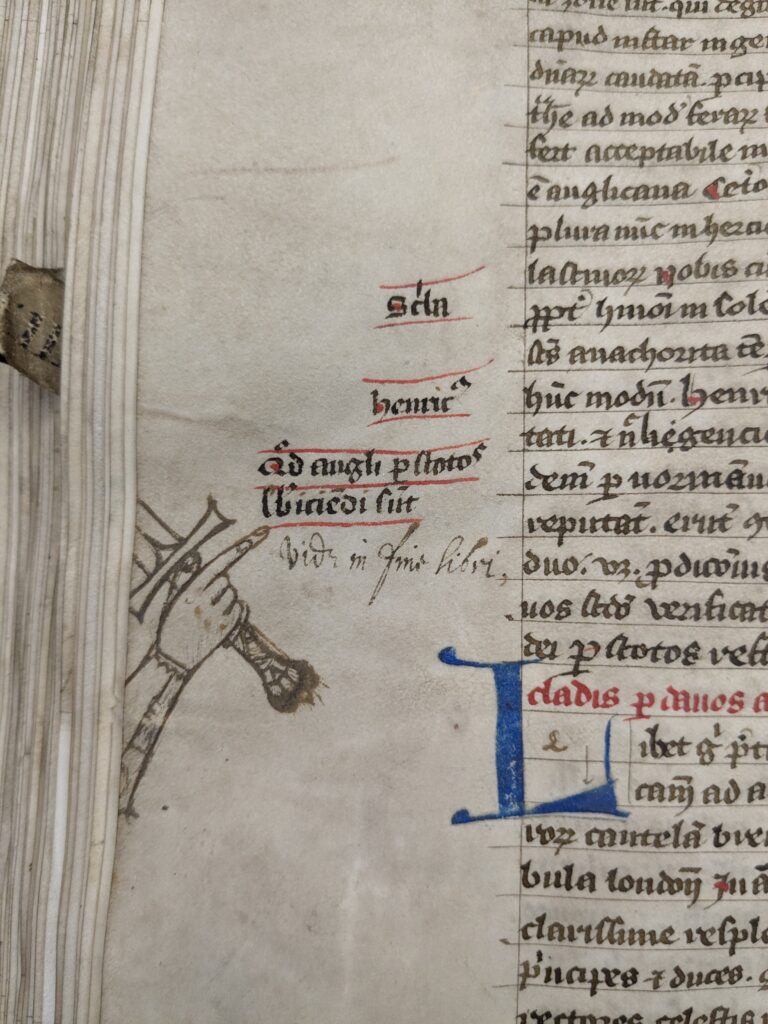

- Fig 2. A fox (f.173r) in the Black Book of Paisley, B.L. MS Royal 13 E.X. (Image Credit: Bryony Coombs)

In each instance, the images have been added by the same later reader to highlight a particularly vehement piece of anti-English rhetoric. The raised hand grasping the ornate hilt of a sword has been added to visually emphasise a key point. The hand has evidently been added over a pre-existing manicule and you can see a longer fingertip protruding from underneath this newer addition. The sword is brandished over a section of text dealing with a holy anchorite in Ethelred’s time who prophesised English downfall at the hands of the Danes, Normans, and Scots. ‘Because the English are given over to treachery and drunkenness and disregard for the house of God, they will have to be crushed first by the Danes, then by the Normans and thirdly by the Scots, whom they regard as worthless.’ Later in the manuscript the same reader draws an arresting image of a small alert fox labelled ‘vulpes’. A fine line connects the drawing to the text of the following verse:

Sculptor, when you carve, make the English like foxes,

And the French like lambs, make well the Normans like great bears

The Britons like boars and the Scots like lions.

The visual additions to Black Book of Paisley, therefore, are visual aids to assist the reader in navigating the text and to draw attention to those areas of anti-English sentiment that struck a chord with the reader and to which they might wish to return.

Whilst these visual aids were added after the completion of the text, other pictorial elements were often added by the scribe in the process of writing. Embellishments of this kind might be seen in another partial copy of the Scotichronicon: BL MS Harley MS 4764. This is a parchment manuscript of 188 folios, 32 x 23cm, written at Dunkeld by a notary public, Richard Striveling, for Bishop George Broun between 1497 and his death in 1515. In this instance Striveling demonstrates a keen eye for the aesthetics of the manuscript, integrating letters embellished with small faces, often enlivened with touches of colour and using ornate cadels that erupt into decorative swirls of birds, deer, and spiralling foliage. On one folio a fallow deer, made identifiable by the carful depiction of marking on its coat, is integrated into the end section of text (Fig. 3). In this instance, the elaboration relates less to the meaning of the words, and more to the aesthetic impact of the work. The scribe demonstrates their skill, but also shows an awareness of producing a visually impressive volume for the reader. The way the text looks on the page is important. A sense of prestige is achieved even without the use of expensive pigments and gold.

A fallow deer, Scotichronicon, B.L. MS Harley MS 4764 (Image Credit: Bryony Coombs)

A final example of imagery integrated into the text can be found in another example of a Scottish history, this time a late-fifteenth century copy of the Liber Pluscardensis: Bodleian MS Fairfax 8. In this instance the manuscript consists of 209 folios of paper and parchment, 28 x 21.5. The catalogue records for this volume make no mention of images and yet there is a plethora of visual material contained within. One particularly intriguing example is the extensive use of pictorial framing for the catchwords. Throughout the manuscript, the catchwords (which identify how quires should be ordered) are held aloft by hastily penned caryatids. These female figures, although sketchily depicted, have wavy hair and often ornate cloaks affixed by a diamond-shaped buckle (Fig. 4). The inclusion of this classicising detail is intriguing. What this tells us about the visual imagination of the scribe is significant when we consider the influence of classical concepts and aesthetics in Scotland at that time, and it remains the subject of my ongoing research.

Catchword caryatids, Liber Pluscardensis, Bodleian MS Fairfax 8 (Image Credit: Bryony Coombs)

In each case examined, we see an attempt to bring the past to life, to make it engaging for the reader. From the addition of marginal images to those images included by the scribe at the time of writing, images were added because they could communicate something that the words could not. In each case the imagery performs a different function; to assist in navigating the text, to draw the reader’s attention, to create the impression of a sumptuous object, or to evoke ideas from a distant past. My new book will explore all of these uses of the visual in manuscripts and more. One point to emerge from the research so far, is that secular texts in Scotland, such as histories, had a stronger visual tradition than has previously been recognised. Such imagery certainly played a role in formulating ideologies. The past then as now supplied the standard against which the present could be evaluated, and images played a crucial role in this. As an activity, therefore, the writing of history represents an important aspect of society’s search for self.

*In March of 2024, myself and colleagues from the History of Art Department at the University of Edinburgh, ran a roundtable seminar on our manuscript research for the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. The event was online and open to members of the society. This was a fantastic opportunity to bring together manuscript scholars working on Scottish material and to promote our research cluster: Edinburgh Manuscripts: Composition and Collection (EMCC). The event encouraged the brining together of expertise, but also allowed this research to reach a wider audience and we are extremely grateful to the Society for facilitating this.

Bryony Coombs is Renaissance Teaching Fellow in History of Art at the University of Edinburgh. Her first monograph, Visual Arts and the Auld Alliance: Scotland, France and National Identity c.1420-1550 will be published by Edinburgh University Press in September 2024, and she has recently signed a contract for her second monograph, Scotland on Parchment: Illuminated Manuscripts in Late-Medieval Scotland with Edinburgh University Press in their new Visual and Material Cultures of Scotland Series. Bryony was elected as a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society (FRHistS) in May 2024 and had been the recipient of the Murray Medal for History (2019, you can read the paper online free here) and the Jack Medal (IASSL, 2021).